Art of the Everyday: Household Labour and Meals in the Seventeenth Century.

Kitchen utensils, spinning wheels and bedsheets. At first sight, those objects seem to be unusual subjects for art historical research. However, those objects tell a lot about life in seventeenth century Netherlands, as can be seen in many artworks.

In a seventeenth century room in the historical Gravensteen Building in the city centre of Leiden, a group of experts in applied arts held a symposium about daily life and several types of objects in this period, which took place at March 24 this year.

Danielle van den Heuvel took off with a lecture about seventeenth century families and households. Late marriage, mass immigration of women, and a high death rate for children caused a female surplus. There were many single mothers, who had to both keep house and provide for an income, for example in spinning, which formed a substantial part of Dutch textile economy.

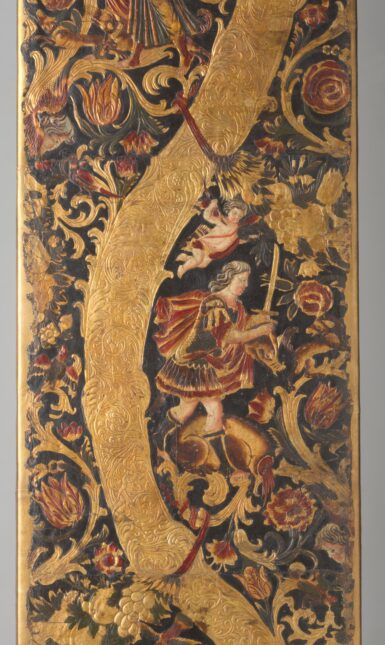

Very different were the lives of the well-off, whose houses were sumptuously furnished and decorated. Lavishly decorated and gilded leather wallpaper was a popular way of decorating, as Eloy Koldeweij told in his lecture. Many designs contained narrative or allegorical elements, like Greek mythological characters or allegories of the Four Seasons or the Five Senses. The leather panels often depicted flower garlands, which could be arranged in different ways to make a pattern.

Tirtsah Levie Bernfeld showed how objects could function to express cultural identities, as was the case with Portuguese Jews in Amsterdam. Christianized in Portugal, they moved to the Netherlands and converted back to Judaism. They showed their regained identity by means of different ritual objects, like shabbat lamps and Passover plates. However, the Portuguese and Dutch cultures are visible as well. Sometimes, these mingle in unexpected ways, for example rimonim (torah finials) in the shape of church towers.

Christianne Muusers told about indispensable kitchen utensils. The most used tools were mortar and pestle, which were used to grind herbs or to make a sauce. Another much used tool was the so-called ‘taartpan’ (pie-pan). Placed in burning coals with a pie in it and with coals on the lid, it was an alternative for the huge built-in stone ovens of the rich.

It is not always clear how objects were used in history. Tim Smeets, from the Dutch Open Air Museum, told about objects in the museum’s collection. Since the museum used to be focused on collecting buildings, many objects from the buildings’ interiors were not properly documented. From the 1950s, objects started to be described and documented. However, there are many remaining questions. Different theoretical, historical, but also experimental, ways of research are used to uncover the objects’ functions.

The last lecture was given by Sanny de Zoete, who spoke about linen and damask, which formed a very important part of seventeenth century inventories. In wealthy households, complete sets of towels, napkins and tablecloth in matching designs, were important status symbols. Mothers passed these linens on to their daughters, and taught them how to repair the textiles. Designs varied from intricate geometrical patterns to flowers and even biblical images. Bed linens were of course a less visible kind of household textiles. They were made of plain linen, but often adorned with lace and embroidery. De Zoete brought some textiles of various kinds to this symposium, so the audience could experience the variety of seventeenth century textiles with their own eyes, and they even held a large bedsheet in their hands.

This symposium showed that, although art historical research is traditionally focused on artworks and special objects, research on normal objects for daily use helps us to understand seventeenth century life, and can bring back the world behind the well-known art.

Hester Be is a student in Art History and Philosophy at Leiden University.

0 Comments