Image Reincarnation: Illustrations of the Ten Avatars of Vishnu assuming New “Lives” in the hands of European Artists and Readers

An evaluation of how the creators’ identity and goals prompted a transcultural evolution of pictorial presentation of deities and religious mythology.

Think about a time when you told a friend a story. That friend enjoyed it so much that they passed it on to someone else, adding slightly different emphases and altering details here and there. This continued from one person to the next until the tale made its way back to you. By this time, the story had evolved so much that you barely recognize it as your own. Each person who retold the account put their own twist on it, meaning that the final version includes bits and pieces of the identities of each of the intermediary storytellers. My dissertation evaluates this phenomenon of a story transforming through retelling. Rather than oral transmission, my work focuses on written accounts paired with images, in both manuscript and published forms. My project titled, Image Reincarnation in Early Modern Dutch Illustrated Travelogues, evaluates a set of ten stories which are foundational to Hindu theology, and how they morphed through retelling. The stories are known as the Dashavatara (from the Sanskrit for ten incarnations) which describe the primary forms in which the god Vishnu manifested himself on Earth for the purpose of divine intervention.

These tales circulated around India and were introduced to Europeans, who traveled to India for mercantile pursuits, in the seventeenth century. Along with material goods, a handful of illustrated versions of the Dashavatara made their way back to Europe. In Amsterdam, authors and engravers integrated their understanding of these stories into the accounts of the Indian subcontinent that they published in the last quarter of the seventeenth century. I use the term “Image reincarnation” in my title to refer not only to the Hindu belief of the transmigration of souls, but also to imply that the images and texts assumed new “lives” each time they were reproduced. In India, the details of Dashavatara varied slightly depending upon the geographical region and the particular sect of Hindu belief to which the creator ascribed. Regardless of these nuances, visual versions of these stories were considered sacred and to be physically embodied by the Divine. When the Dashavatara made its way into European hands, significant elements were lost and edited in translation. As the figures and their surroundings changes, the purpose of the images did too. Rather than sacred images to meant to prompt worship, in a European context the avatar images ranged from entertaining to educational and were meant to inspire the purchase of the books in which they appeared.

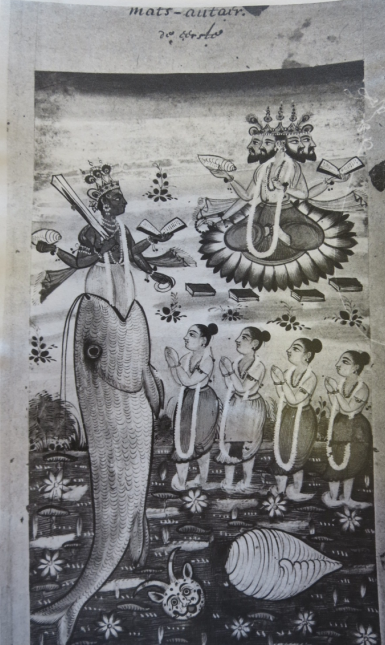

Philips Angel, a Dutchman, penned a Dutch version of the story of the Dashavatara in 1658, which was accompanied by water-colored illustrations by an unknown Indian artist. The first incarnation of Vishnu is in the form of a fish known as Matsya Avatar.(fig. 1) Philip Baldaeus, who lived in South Asia for about a decade, and Olfert Dapper, who never left the Netherlands, both included versions of the ten incarnations in their travelogues about India which were published in Amsterdam in 1672. In Baldaeus (fig. 2) and Dapper (fig. 3), Matsya Avatar features Vishnu’s human-like torso emerging from the mouth of a large fish with his four arms holding his attributes. Brahma, the Creator god, a four headed and four-armed deity sits cross-legged upon a lotus blossom in both compositions. It is thought that the illustrations in Angel’s manuscript were inspiration for both Baldaeus and Dapper’s engravers. Both Dapper and Baldaeus’ Matsya Avatar are set in a landscape that provides a sense of depth and atmosphere including the requisite palm trees denoting exotic location. The similarities with one another and Angel’s do not extend much further. Dapper’s scene appeals more to European tastes in painting through heavy application of chiaroscuro and a scene crowded with figures.

The other most eye-catching aspect of Dapper’s Matsya is the form of Vishnu himself. The deep black skin and strong muscles make him look more as if he is of African origin than the blue-black of Hindu tradition. This skin tone and musculature is matched only by that of the beheaded torso leaning on his shield the foreground. Blood spurts forth from this figure in a manner that evokes that of Caravaggio’s Judith Slaying Holofernes(1599), or the plucky knight with a mere flesh wound from Monty Python’s Holy Grail. The overall effect of Dapper’s scene is fantastical, exotic, and theatrical aimed at entertainment. Baldaeus’s more simplified images were accompanied by a text drawing parallels to the Old Testament and Greek and Roman authors-potentially inciting intellectual conversations concerning religion. Each of these new renditions of the Avatars of Vishnu are presented through a differing European lens, aimed at a European audience. Travelogues presented version of India that existed only in the minds of their creators marketed toward their targeted readers.

Margaret Mansfield is a PhD Candidate in history of art and architecture at the University of California, Santa Barbara and his currently a Samuel H. Kress Institutional Fellow at Leiden University. In addition to her dissertation she is working on a collaborative project based at the University of Minnesota, focusing on Bernard Picart’s Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde. For more information about her scholarship follow this link: https://www.arthistory.ucsb.edu/people/margaret-mansfield

0 Comments